DARK AGE (1987)

Dir. Arch Nicholson

Crocodilian chaos in Australia’s Northern Territory: When one particularly big brute starts snacking on humans, it’s up to wildlife ranger and conservationist Steve Harris (John Jarratt) to bring it to heel. With a sensible respect for the local wildlife, Steve wants to stop the killer croc while preventing a crew of mad hunters (eager for an excuse to indulge their bloodlust) from hitting the creeks for a pump-action killathon.

Crocodilian chaos in Australia’s Northern Territory: When one particularly big brute starts snacking on humans, it’s up to wildlife ranger and conservationist Steve Harris (John Jarratt) to bring it to heel. With a sensible respect for the local wildlife, Steve wants to stop the killer croc while preventing a crew of mad hunters (eager for an excuse to indulge their bloodlust) from hitting the creeks for a pump-action killathon.

Aboriginal elders warn Steve that this ain’t no ordinary crocodile: In addition to its size, this creature is “proper old” and “wise,” they say. He’s also a figure in their Dreaming and they refuse to participate in killing him. The initial attack is provoked by the incursions of racist poachers, and Dark Age carries a strong anti-colonial subtext, evoking a land stolen and its ecology ignored and degraded.

The largest reptile on earth, and with the gnarled look of a nasty dinosaur, the saltwater croc’s menace is wonderfully evoked with reference to its prehistoric origins (hence the film’s title), as well as its role in a timeless Aboriginal spirituality. In a nod to Jaws, the local bigwig (played by Home and Away veteran Ray Meagher) is concerned about tourism: Japanese investors set to build the town up mustn’t be scared off.  Ultimately, Dark Age depicts an outback culture whose powerful players are in hot pursuit of modernization and money, trying to leave behind an indigenous history—and present—to which the creature is connected. The subtext comes on a little strong at one or two points, but amid numerous less imaginative Jaws-imitators it’s refreshing to see a film so brimming with ideas.

Ultimately, Dark Age depicts an outback culture whose powerful players are in hot pursuit of modernization and money, trying to leave behind an indigenous history—and present—to which the creature is connected. The subtext comes on a little strong at one or two points, but amid numerous less imaginative Jaws-imitators it’s refreshing to see a film so brimming with ideas.

The film’s score, heavy on the synth drums, is at times distractingly dated, and can’t always summon the intensity required (especially during a Jaws-like pursuit of the predator). The crocodile effects are also limited and sometimes log-like: one shot of the croc on the water’s surface seems to terminate because the model is slowly drifting off to the left. Shots of the brute in motion could have been livened up with some strategically edited and inserted stock footage. That aside, the film invests properly in its human drama, and tensions within the town (and culture more broadly) are played out through strong performances. As implied above, though, the film is perhaps most effective in its evocation of Australia as a kind of haunted land: a place with an ancient identity of which its white inhabitants are ignorant, but which nevertheless bursts violently forth from the past—and bites. 3.5 / 5

The film’s score, heavy on the synth drums, is at times distractingly dated, and can’t always summon the intensity required (especially during a Jaws-like pursuit of the predator). The crocodile effects are also limited and sometimes log-like: one shot of the croc on the water’s surface seems to terminate because the model is slowly drifting off to the left. Shots of the brute in motion could have been livened up with some strategically edited and inserted stock footage. That aside, the film invests properly in its human drama, and tensions within the town (and culture more broadly) are played out through strong performances. As implied above, though, the film is perhaps most effective in its evocation of Australia as a kind of haunted land: a place with an ancient identity of which its white inhabitants are ignorant, but which nevertheless bursts violently forth from the past—and bites. 3.5 / 5

RAZORBACK (1984)

RAZORBACK (1984) Meanwhile, grizzled pig-shooter Jake (Bill Kerr), grandfather of the stolen baby, begins a Quint-like quest against the beast. Regrettably, Jake is but a shadow of his animal-horror influences, and the film suffers here from its indecisive tone: it’s hard to develop a scarred and serious character in a circus like this. Leaving that aside, Razorback is stylish and garishly striking—fairly well-financed but shot with an irresistible exploitation verve. The final showdown with the big boy (with much organ-pounding over the soundtrack) is sort of scarier than the rest of it, but foremost a silly delight. 3.5 / 5

Meanwhile, grizzled pig-shooter Jake (Bill Kerr), grandfather of the stolen baby, begins a Quint-like quest against the beast. Regrettably, Jake is but a shadow of his animal-horror influences, and the film suffers here from its indecisive tone: it’s hard to develop a scarred and serious character in a circus like this. Leaving that aside, Razorback is stylish and garishly striking—fairly well-financed but shot with an irresistible exploitation verve. The final showdown with the big boy (with much organ-pounding over the soundtrack) is sort of scarier than the rest of it, but foremost a silly delight. 3.5 / 5 An intense and aggressive domestic drama descends into experimental horror in Żuławski’s cult classic Possession. Steered visually by the restless cinematography of Bruno Nuytten the film constructs a world pervaded by uncertainty, discomfort, and a sense of worse to come. The initial horror is of an everyday nature: Mark (Sam Neill) arrives home to Berlin to discover his wife Anna (Isabelle Adjani) has been having an affair and is not the least bit sorry about it either. He turns on the insecure male hysterics and quickly drives her to a similar pitch—then beyond. However, in an apartment downtown Anna has been keeping (and gradually growing) a more monstrous secret, and as her behavior becomes more and more unhinged the film explodes into a warped and chaotic exploration of loathing, desire, and frustration.

An intense and aggressive domestic drama descends into experimental horror in Żuławski’s cult classic Possession. Steered visually by the restless cinematography of Bruno Nuytten the film constructs a world pervaded by uncertainty, discomfort, and a sense of worse to come. The initial horror is of an everyday nature: Mark (Sam Neill) arrives home to Berlin to discover his wife Anna (Isabelle Adjani) has been having an affair and is not the least bit sorry about it either. He turns on the insecure male hysterics and quickly drives her to a similar pitch—then beyond. However, in an apartment downtown Anna has been keeping (and gradually growing) a more monstrous secret, and as her behavior becomes more and more unhinged the film explodes into a warped and chaotic exploration of loathing, desire, and frustration. possible identification or sympathy, risking a kind of objectifying ‘insanity porn’—a display foremost for our shock and amazement. Or perhaps in its transgressive and apocalyptic intensity (far beyond narrative or meaning) the moment achieves a kind of liberatory chaos? I expect opinions vary.

possible identification or sympathy, risking a kind of objectifying ‘insanity porn’—a display foremost for our shock and amazement. Or perhaps in its transgressive and apocalyptic intensity (far beyond narrative or meaning) the moment achieves a kind of liberatory chaos? I expect opinions vary. Good old-fashioned revenge doesn’t get much better than this down and dirty lead crusade from Giulio Petroni. On the kind of sodden night from which nothing good can come a gang of hoods storm the home of the young Bill Meceita, murdering both his parents. 15 years later, all grown up and more than handy with a gun, Bill (John Phillip Law) sets out for revenge. Meanwhile, Ryan (Lee Van Cleef), an outlaw as weathered as the rocks he splits during his term of hard labor, is finally granted release and begins his pursuit of the crooks who double-crossed him into the slammer in the first place. You guessed it: they’re the same low-lives.

Good old-fashioned revenge doesn’t get much better than this down and dirty lead crusade from Giulio Petroni. On the kind of sodden night from which nothing good can come a gang of hoods storm the home of the young Bill Meceita, murdering both his parents. 15 years later, all grown up and more than handy with a gun, Bill (John Phillip Law) sets out for revenge. Meanwhile, Ryan (Lee Van Cleef), an outlaw as weathered as the rocks he splits during his term of hard labor, is finally granted release and begins his pursuit of the crooks who double-crossed him into the slammer in the first place. You guessed it: they’re the same low-lives. Although the film’s main interest is action—the simple pleasure of watching a couple of tough hombres take care of business—Petroni’s stylistic flair lends a symbolism of its own to these proceedings. The treachery and isolation of the Western landscape, the inexorability of fate, and the development of a surrogate father/son relationship between Ryan and Bill are all evoked.

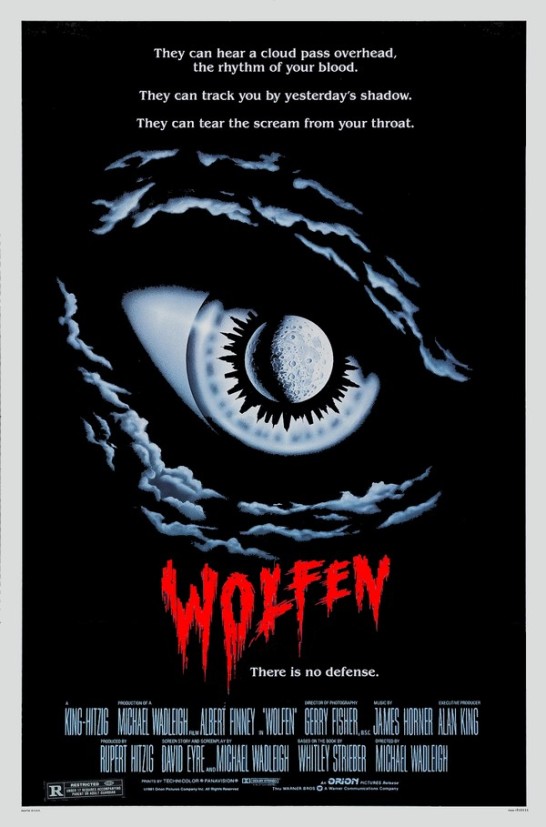

Although the film’s main interest is action—the simple pleasure of watching a couple of tough hombres take care of business—Petroni’s stylistic flair lends a symbolism of its own to these proceedings. The treachery and isolation of the Western landscape, the inexorability of fate, and the development of a surrogate father/son relationship between Ryan and Bill are all evoked. WOLFEN (1981)

WOLFEN (1981) This theme is hauntingly imbued in images of industrial and residential dilapidation—urban rubble through which the wolves stalk their prey. As Wilson tracks his targets, a tingling, stealthy score by James Horner accents (and never smothers) the film’s shivery atmosphere. A film as dark, graceful and bewitching as its elusive antagonists. 5 / 5

This theme is hauntingly imbued in images of industrial and residential dilapidation—urban rubble through which the wolves stalk their prey. As Wilson tracks his targets, a tingling, stealthy score by James Horner accents (and never smothers) the film’s shivery atmosphere. A film as dark, graceful and bewitching as its elusive antagonists. 5 / 5 The golden age of radio drama may be in the past, but audiobook subscription service Audible supplies an enthralling extension to the saga of Warrant Officer Ellen Ripley, and of creatures and memories that also refuse to be left behind. The play is approximately novel-length (indeed based a novel by Tim Lebbon) and divided into chapters of around 25-30 minutes long, complete with not merely dynamic voice performances, but also sound-effects and a score—by turns eerie, momentous and mournful—to bring the production to vivid, egg-opening life.

The golden age of radio drama may be in the past, but audiobook subscription service Audible supplies an enthralling extension to the saga of Warrant Officer Ellen Ripley, and of creatures and memories that also refuse to be left behind. The play is approximately novel-length (indeed based a novel by Tim Lebbon) and divided into chapters of around 25-30 minutes long, complete with not merely dynamic voice performances, but also sound-effects and a score—by turns eerie, momentous and mournful—to bring the production to vivid, egg-opening life. The narrative picks up after the events of the first film as Ripley’s escape pod is intercepted by the crew of a mining vessel, who begin having a xenomorph problem of their own. Consequently Ripley, here played with all the characteristic mannerisms by Lauren Lefkow, is on hand to tell them how fucked they are—before becoming the key adviser against the threat. Meanwhile, android Ash, played by (and dismembered as) Ian Holm in the original film and now performed by Rutger Hauer, is up to old tricks. Hell-bent on fulfilling his mission for the Company of transporting an intact alien specimen, Ash’s disembodied artificial intelligence infiltrates and contaminates various ship systems to sabotage this new team’s efforts. Conceptually and tonally, the film strikes a balance between the first and second films, combining the original’s focus on malignant AI and a crew under-prepared for the menace they face with plenty of action as the creatures close in.

The narrative picks up after the events of the first film as Ripley’s escape pod is intercepted by the crew of a mining vessel, who begin having a xenomorph problem of their own. Consequently Ripley, here played with all the characteristic mannerisms by Lauren Lefkow, is on hand to tell them how fucked they are—before becoming the key adviser against the threat. Meanwhile, android Ash, played by (and dismembered as) Ian Holm in the original film and now performed by Rutger Hauer, is up to old tricks. Hell-bent on fulfilling his mission for the Company of transporting an intact alien specimen, Ash’s disembodied artificial intelligence infiltrates and contaminates various ship systems to sabotage this new team’s efforts. Conceptually and tonally, the film strikes a balance between the first and second films, combining the original’s focus on malignant AI and a crew under-prepared for the menace they face with plenty of action as the creatures close in. This new story is thrilling and energetic, yet retains the technical flourishes that helped plausibly underpin the films. The only let-down here is that while the drama initially presents as an ‘alternative’ timeline, later turns of the narrative work to re-integrate what has happened into the existing Alien chronology in a manner that seems clunky and unnecessary. Nevertheless, this hardly makes much of an acid burn on such an gripping and gorgeous production. A must for fans of the franchise. 4.5 / 5

This new story is thrilling and energetic, yet retains the technical flourishes that helped plausibly underpin the films. The only let-down here is that while the drama initially presents as an ‘alternative’ timeline, later turns of the narrative work to re-integrate what has happened into the existing Alien chronology in a manner that seems clunky and unnecessary. Nevertheless, this hardly makes much of an acid burn on such an gripping and gorgeous production. A must for fans of the franchise. 4.5 / 5 QUATERMASS AND THE PIT (1967)

QUATERMASS AND THE PIT (1967)

CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON (1954)

CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON (1954) and fins, the monster is also conspicuously anthropomorphic, and the suggestion of our continuity with so strange a cousin provokes unease through a blurring of the human-animal binary.

and fins, the monster is also conspicuously anthropomorphic, and the suggestion of our continuity with so strange a cousin provokes unease through a blurring of the human-animal binary.